Sad Moscow airport selfie.

I put my blue paper mask on when I saw I would be seated next to a tiny old woman on the 11-hour flight from Moscow to New York. I heard that masks don’t do much to prevent getting sick, they only curb the spread of your own germs. She had all-white hair and dark eyes and was about as tall as the seat backs on the plane. I offered to help her put her jacket in the overhead bin, she made a comment about me being very tall, and then we settled in for the long haul to the epicenter of the virus in the U.S.

Her name was Inara. We talked a bit while other passengers filed past — students coming home early from a semester abroad, couples who had decided to cut their vacations short and several young people who appeared to be a part of some kind of youth missionary group, all dressed up and wearing name tags I couldn’t read all found their seats in the Airbus that only ended up being half-full (half-empty?) by takeoff.

Inara was born in the USSR, in Yerevan (today’s capital of Armenia) before moving to Moscow and then eventually to the U.S. She was visiting Moscow and had planned to stay until the end of the month, but Turkish Airlines was canceling flights left and right so she decided to return earlier. I told her I was supposed to stay in Russia longer too, but had decided to leave while it was still relatively easy to make it back to my family.

“You know, we have this saying in Russia,” she said, “‘God…’” and then I have no idea what she said after that. She used a verb I wasn’t familiar with and maybe a grammar construction I didn’t understand, but she was patient and explained that we can’t always wait for God to make decisions for us, sometimes we have to make choices for ourselves and that’s just the way it is (or something along those lines — it had been about a week since I had gotten more than four hours of sleep and the ol’ noodle was suffering.).

A few days earlier, I had been sure that I would see this pandemic through while I continued my life in Novosibirsk. But then things started going downhill real fast and I watched via social media as Boren Scholars, Peace Corps volunteers and other Fulbrighters were all called home. My university had decided to extend its two weeks of distance learning to at least a month. The first cases of the virus had been confirmed in Novosibirsk. And after an intervention-esque conversation with my mom, sister, aunt and uncle, I decided it was time to go home (if for nothing but my mother’s peace of mind.).

Well — I was, like, 80% decided. There’s an 11-hour time difference between the east coast and Novosibirsk, which meant that as I went about my day, I wasn’t getting many news updates about closing borders or death tolls nor any messages from friends and family asking if I would return to the States. And because it was all business as usual in Siberia, I felt so removed from the catastrophe. It was easy to ignore. This was what was most difficult — I’d go from feeling absolutely certain that remaining in Russia was the right choice to feeling stupid for not already leaving. It really tore me up. The uncertainty settled heavy in the pit of my stomach and I couldn’t sleep. But ultimately it came down to two things, 1) would I rather be quarantined in a city of almost 2 million people or at home in the mountains? and 2) would I be okay being 24+ hours of travel away from my family should, God forbid, anything happen to them? With my answers decided, I pulled up Aeroflot flights to JFK.

I messaged Marisa, a fellow Fulbright Russia ETA who I admire for her brilliant candidness, to ask how she had decided to leave. She listed a lot of the logistical reasons that had been rattling around my brain for days, but she also said the whole process required a lot of grieving. In was amazed that she was able to so accurately put a word to it: grief. As I packed my bags in the days leading up to my departure, I would be hit by waves of disbelief and sadness, and I was surprised by the familiarity of the feeling. Since my dad died, I’ve spent a lot of time considering the what-could-have-beens, the unrealized experiences we should have had and I mourn the loss of those experiences. It’s almost the same now — the opportunity to further develop relationships with all my students is gone, I won’t be celebrating Victory Day in a crowded Lenin Square or returning to Irkutsk to see Baikal in the summer, and my friends at the climbing gym will keep climbing new routes and I won’t be there to cheer and laugh and fall and chat.

I am lucky and loved living the life I lived with my dad in it; I am lucky and loved living in Novosibirsk with people I admire. Loss is difficult in both cases.

I am fully aware I write this at the risk of sounding self-indulgent/absorbed or dismissive. This is all very “me me me.” Perhaps your’e annoyed after reading this far or maybe you’re recalling that episode of Keeping Up With The Kardashians when Kim is distraught over losing her diamond earring in the ocean and her sister calls up from the blue water, “Kim, people are dying.”

I’m not saying coming home is absolutely comparable to losing a loved one, a reality that tens of thousands of people are coping with in this crisis. People all over the world are suffering, and my losses are few compared to most. I hope that talking about grief and loss in this way doesn’t seem like I’m diminishing the pain of lives lost — I’ll note that' it’s been five years and I’m still shattered by my dad’s death. Conversely, I left Russia a week ago and I’m doing fine now. There are different kinds of grief, but I think all are life-changing. If I had understood the gravity of the situation a week ago as I do now, maybe I would’ve been less devastated or at least less self-absorbed. Or maybe not.

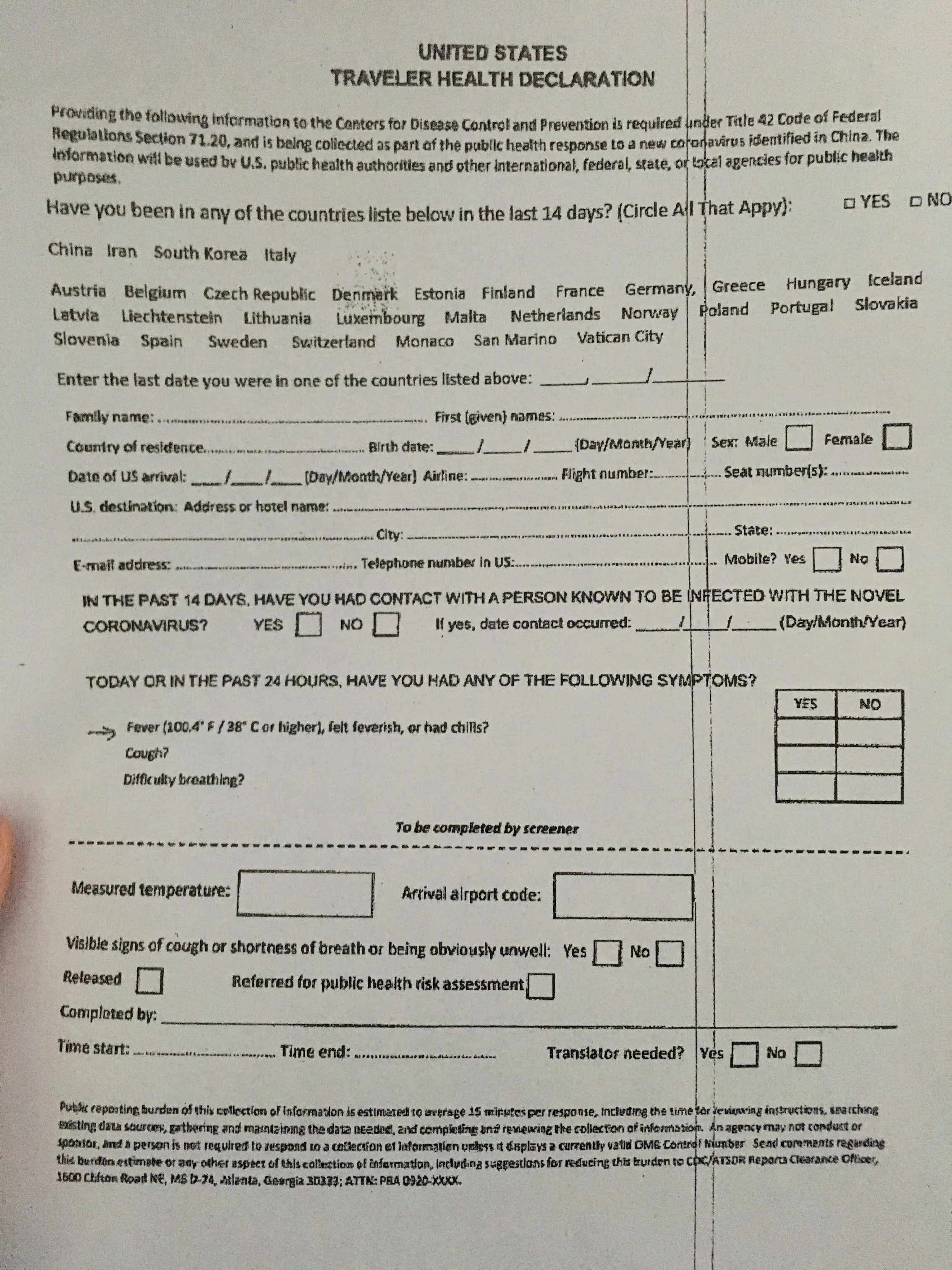

For anyone curious, this is what we had to fill out on the flight (that no one collected or even glanced at!).

I’m so lucky that I had a wonderful place to return to in the U.S. and the financial capabilities/good health to make the journey safely. On Wednesday the 18th, I bought a ticket to head home on the 22nd. On Friday the 20th the State Department issued a Level 4 travel advisory, and I bumped my flight up to leave on Saturday the 21st. After 24 hours of traveling I landed at JFK at 6:30 pm on Saturday (time zones are weird) to an unsettling lack of health screenings. I didn’t see anyone get their temperature checked, not even the couple that had been sitting in the row in front and to the right of me who had spent the entire flight coughing and not covering their mouths (I couldn’t sleep on the flight because I was staring and quietly directing my fury at the pair — couldn’t they see precious Inara sitting next to me? I should’ve said something.). We filled out health surveys on the flight but no one ever collected them — that was the extent of it.

After the new travel advisory was issued, Fulbright decided to suspend all its programs and, from what I understand, even the participants who were committed to staying in their host countries had to return home.

I landed in JFK, sleep-deprived and sweaty — wearing several layers to economize suitcase space was fine in freezing Novosibirsk but considerably less ideal in a nearly 70*F New York. The last bit of Russian I’ll use for a while was a final exchange with Inara at the baggage claim (“Why did they make us fill out these papers if no one is even taking them?” she laughed, waving the health survey at me.).

And now, a full three months ahead of schedule, I’m at my mom’s kitchen table in Thornton, New Hampshire. I’ve been home with Betsy and Meg for a week and the majority of this quarantine has been spent doing yoga and taking long walks in the woods (we’re like the world’s smallest hippie commune.). I miss my students and their enthusiasm and humor. I miss my gym friends Dasha and Genya, who mean more to me than I can express and had way more faith in my climbing skills than was reasonable. I miss Olesya and Dima, who provided friendship and comfort from my very first moments in Novosibirsk. I miss seeing Siobhan everyday and discussing the Russian peculiarities that shaped our everyday experiences.

But that’s the way it is. The snow is still melting and the sky is still blue and the days will keep tumbling past us until this is over — and I’m glad I’m with my mom and sister until that time comes. I’ve been laughing so much the last few days that I really think I’m going to come out of this quarantine with some pretty sculpted abs. So in short, here’s what what I’m grateful for today: to be spending an unprecedented amount of time with my favorite funny ladies, for the internet keeping me connected to folks who live thousands of miles away, and for having the kind of love for Novosibirsk that made saying goodbye so very difficult.

![IMG_0868[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572588098246-QH8IP2OSS7H8LEHSEEV5/IMG_0868%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0860[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572588083088-W4JJVORJ27OWYTODZ5LE/IMG_0860%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0845[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572588168103-09EOO04WT2K7631ZYH54/IMG_0845%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0704[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572587773018-T7RBCOFVX1TV8C7JNZ4Y/IMG_0704%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0811[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572587835248-QVQZYOTN652TGDNCZLJV/IMG_0811%5B1%5D.JPG)

![IMG_0575[1].JPG](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c26437a75f9ee1e3085da19/1572587592291-2MN310KCQ05CEN0TBHRC/IMG_0575%5B1%5D.JPG)